I found this note in the Harry A. Williamson Papers at the Schomburg Center while doing research for Black Gotham. It’s a central document in my “cluster” on the New York City draft riots and uncovers a fascinating story. The first part of the story relates to Williamson’s identity. He turns out to be the grandson of Albro Lyons, the man to whom the note is addressed. Williamson’s extensive collection testifies to his determination to preserve his family’s history; it includes genealogical records as well as a short memoir by one of Lyons’s daughters, Maritcha (and his aunt).

I found this note in the Harry A. Williamson Papers at the Schomburg Center while doing research for Black Gotham. It’s a central document in my “cluster” on the New York City draft riots and uncovers a fascinating story. The first part of the story relates to Williamson’s identity. He turns out to be the grandson of Albro Lyons, the man to whom the note is addressed. Williamson’s extensive collection testifies to his determination to preserve his family’s history; it includes genealogical records as well as a short memoir by one of Lyons’s daughters, Maritcha (and his aunt).

Although I didn’t realize it at first, I soon discovered that the Lyonses are part of my family as well! In combing through Williamson’s papers I found out that my great-great-grandfather Peter Guignon married one Rebecca Marshall in 1840, and that Albro married her sister Mary Joseph that same year. That makes Albro my great-great-granduncle. Many years later Philip White would marry Peter and Rebecca’s daughter, Elizabeth.

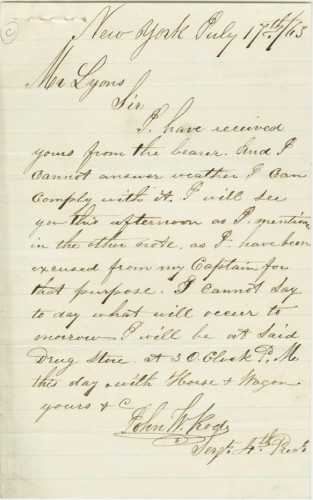

So this note has a particular emotional resonance for me. It was sent by one Sergeant Rode to Albro on the last day of the draft riots. The cause of the riots was the federal government’s passage of a draft law decreeing that all male citizens (by definition white) between the ages of 20 and 35 were to be enrolled in the military, and a lottery conducted to determine who would actually serve. New York’s white working class was angered by what they perceived to be the unfairness of the law. Political elites, who had decided on war, could buy their way out of the draft; African Americans, deemed to be the cause of the war, were excluded by law from service. So on July 13, the mob, composed mainly of Irish men and women, took to the streets, wantonly attacking people and property, particularly in the black community.

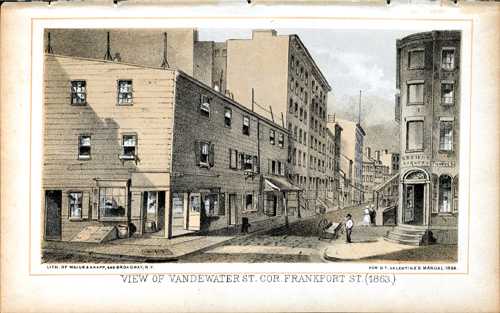

Albro Lyons lived at 20 Vandewater Street. The print above shows a typical Lower Manhattan street mixing buildings both residential and commercial, tall and low, frame and brick. Maritcha had noted in her memoir that the family lived in a large brick building, so it could well have been one of those on the left side of the street. It combined both the Lyons household and a Colored Sailors Home, and was also a stop on the Underground Railroad. The mob stormed it three times. When they had finished, this is what Maritcha had to say about the state of her home: “Its interior was dismantled, furniture was missing or broken. From basement to attic evidences of the worst vandalism prevailed. A fire, kindled in one of the upper rooms, was discovered in time to prevent a conflagration.”

The rioters’ goals in attacking Albro’s home were multiple but precise: they sought to strike at the heart of the black family; destroy black property and wealth, which they saw as ill gotten and undeserved; undermine black enterprises; prevent black sailors from seeking “white” work on the docks; and finally eliminate a black community institution dedicated to the abolitionist cause.

What really caught my eye in the note, however, was the reference to “said drugstore.” Could that have been the drugstore that Philip White had established in 1847 and would keep until his death in 1891? Philip lived onVandewater Street only a few doors from the Lyonses. Look again at the print. If, instead of going up Vandewater you turned left onto Frankfort, at the very next corner you’d come to Philip’s pharmacy. Like Lyons’s Sailors Home, it was an important landmark in the black community. When visiting New York some years earlier, black Bostonian William C. Nell had praised Philip as a “practical man” who “conducted his business, preparing medicines, etc., etc., etc. with as much readiness and skill as any other disciple of Galen and Hippocrates.”

How could Philip’s drugstore have been a safe meeting place for a white police officer and a black victim gathering up his few remaining earthly possessions? Williamson gives us the answer in an account he preserved in his papers and must have provided to the New York Times at the time of Philip’s death. According to the Times obituary:

"When the riot was at its height a crowd of men gathered at White’s store to defend it from attack. Mr. White was warned by some of the business men that he would be wise if he hid himself. He said: `What have I to fear? Even if these men here could not protect me, there are as many men among the rioters who would fight for me as there are those who would injure me.’ Not the slightest attempt was made to harm him or his property."

Unlike Albro, Philip had made himself indispensable to his local neighborhood. As the Times obituary noted, he “was never unmindful of the poor, and the services and material of his store were willingly given without pay to any one who needed them. . . . Scores of poor families were befriended and helped by him not only with medicines, but with food and money. Those whom he helped had a chance to show their gratitude during the draft riots of 1863.”

Philip had achieved a delicate balance in forging a mutually interdependent relationship between himself and his poor Irish neighbors. By giving away medicines for free, Philip was helping to maintain the stability of the neighborhood in which he lived and worked, and protect his own position within it. Accepting his benevolence over the years, his poor Irish neighbors were able to repay him by protecting him during the riots. In so doing, they were also ensuring that the drugstore on which they depended so heavily would survive the riots and continue to serve them.

Carla L. Peterson is professor of English at the University of Maryland. She currently is completing a faculty fellowship at MITH. This post originally appeared at Black Gotham Archive on March 13, 2012.